Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) is a perennial herb belonging to the Apiaceae family, closely related to carrots. Native to Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, this versatile plant has been embraced worldwide for its culinary and aromatic uses. Sweet fennel, known for its distinctive anise-like flavor, plays a key role in various dishes and is famously used in absinthe production.

In its natural habitat, fennel thrives as a hardy perennial but can become invasive in some regions, particularly in the wild where it is considered a noxious weed. Its adaptability, coupled with its unique flavor, makes it a popular choice for gardens, kitchens, and traditional remedies alike.

| Common name | Bronze Fennel, Fennel, Finocchio, Florence Fennel, Sweet Fennel |

| Botanical name | Foeniculum vulgare |

| Family | Apiaceae |

| Species | vulgare |

| Origin | Southern Europe and the Mediterranean |

| Life cycle | Perennial |

| Plant type | Edible |

| Hardiness zone | 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| Sunlight | Full Sun |

| Maintenance | Low |

| Soil condition | Clay |

| Soil ph | Acid |

| Drainage | Well-Drained |

| Spacing | Less than 12 in. |

| Harvest time | Fall |

| Flowering period | Summer |

| Height | 4 ft. – 6 ft. |

| Flower color | Gold, Yellow |

| Leaf color | Gold, Yellow |

| Fruit color | Green |

| Stem color | Green |

| Fruit benefit | Edible |

| Leaf benefit | Edible |

| Flower benefit | Edible |

| Garden style | Butterfly Garden |

I. Appearance and Characteristics

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) is a flowering plant species in the carrot family. It is a hardy, perennial herb with yellow flowers and feathery leaves. It is indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean but has become widely naturalized in many parts of the world, especially on dry soils near the sea coast and on riverbanks.

Fennel came into Old English from Old French fenoil which in turn came from Latin faeniculum, a diminutive of faenum, meaning “hay”.

Foeniculum vulgare is a perennial herb. The stem is hollow, erect, and glaucous green, and it can grow up to 2.5 meters (8 feet) tall. The leaves grow up to 40 centimeters (16 inches) long; they are finely dissected, with the ultimate segments filiform (threadlike), about 0.5 millimeters (1⁄64 in) wide. Its leaves are similar to those of dill, but thinner.

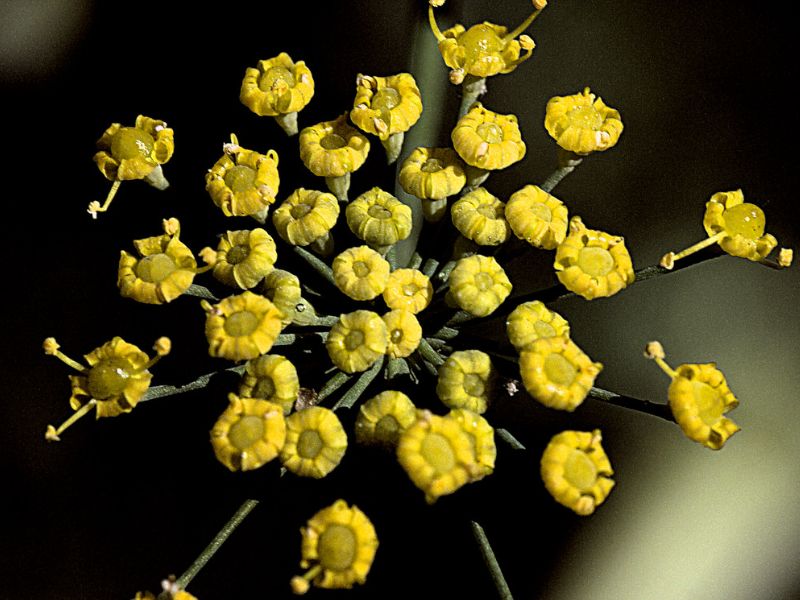

The flowers are produced in terminal compound umbels 5–17.5 cm (2–7 in) wide, each umbel section having 20–50 tiny yellow flowers on short pedicels. The fruit is a dry schizocarp from 4–10 mm (3⁄16–3⁄8 in) long, half as wide or less, and grooved. Since the seed in the fruit is attached to the pericarp, the whole fruit is often mistakenly called “seed.”

II. How to Grow and Care

Watering

Sweet fennel requires consistently moist soil throughout its growing seasons. If you see them wilt, or they are growing slowly, increase watering intervals. Drip irrigation systems, or timed soaker hoses can be a good investment to ensure a robust crop.

Fertilizing

Plant sweet fennel in well-composted soil; this can also be mixed with a balanced, slow-release fertilizer. Once the bulbs develop, feed them with a liquid high-nitrogen fertilizer with NPK ratios similar to 21-0-0; this can be repeated every two weeks until harvest.

Planting Instructions

If you want to grow fennel in the spring, it’s best to start seeds indoors four to six weeks before the last frost date for your region.

Remember, this is a cool-weather crop. If it gets too hot or dry, it may bolt, or run to seed.

Also, because of the temperamental taproot, it’s wise to use seed starter cells that biodegrade, and transplant them in their entirety to the garden after the danger of frost has passed.

Alternatively, you can direct sow seeds into the garden in late summer or early fall, after the worst of the summer heat is over.

It is a commonly held belief that fennel doesn’t get along well with other herbaceous plants, especially those in the Apiaceae family. Don’t sow it in close proximity, to avoid cross-pollination and adverse effects on flavor.

Choose a location that receives full sun. The soil should be organically rich, well-draining, loose loam. According to the Herb Society of America, the ideal soil pH is somewhere in the range of 4.8 to 8.2.

If you don’t know the composition or pH of the earth in your garden, conduct a soil test through your local agricultural extension service, and amend as needed with compost or other rich organic matter, sand for better drainage, and lime to sweeten overly acidic soil.

Work the soil until it’s crumbly, to a depth of about 12 inches. Add amendments as needed.

Sow seeds a quarter of an inch deep and cover them over with soil.

Place the seeds about four to six inches apart, and allow a walkable 12 to 18 inches between rows, if you are mass planting.

Keep the soil moist during the germination and seedling phases.

However, avoid soggy soil, as it makes seedlings prone to a fatal fungal condition called “damping off,” which causes them to fall over and die.

When seedlings have two sets of true leaves, you can thin them to a distance of 12 to 18 inches apart.

Transfer seeds started indoors to the garden at this time. Let them acclimate to the outdoors by remaining in their seed starter pots for a day or two to harden off before transplanting into the garden.

Continue to water young plants regularly but avoid oversaturation and pooling of water to prevent rotting.

An inch or two of rain per week, or equivalent watering, is usually adequate, although there may be occasions that warrant more.

Bulb varieties are less able to handle dry spells than common types. They are also susceptible to “tip burn,” a condition in which insufficient watering may inhibit calcium uptake and cause the edges of the layers to turn brown.

Avert trouble with proper watering and harvest when the bulbs are young and about tennis ball sized, as opposed to older and larger.

You may fertilize Florence plants when the bulbs start to form.

Do not apply fertilizer before plants are well established. Seedlings that receive too much nitrogen may be at increased risk for damping off.

Common F. vulgare blooms near the end of its growing season. If you don’t want it to drop seeds, you can cut the flowers off and remove them before they begin to fade.

In addition to its value as an edible, it provides an attractive, texturally-rich backdrop in the garden, particularly when it’s a bronze variety.

If you are growing Florence types you can keep the bulbs snowy white by mounding soil or mulch up around them when the vegetables first begin to swell.

This technique is called “blanching,” and provides protection from browning in the sun.

Adding mulch over the top of the bulb-like roots of the Florence varieties ensure that they remain white and more satisfying in culinary endeavors.

When bulbs are harvested young, at no more than four inches across, there may be no flower bud development at all.

If there is, you can snip the ends off the foliage to prevent bud formation, seed drop, and potentially invasive growth.

You can also try growing fennel in containers on a patio or balcony. Two things to remember are:

- You’ll need a pot at least two feet deep to accommodate the long taproot.

- Pots dry out quickly, so be vigilant with watering.

In both containers and the garden, plants may require support. A few bamboo garden stakes and some twine can provide the needed stability.

If you’re growing common F. vulgare, you can prune it down by one-third in early summer for a more compact shape.

Note that in areas where summer heats up quickly, you may be better off planting in mid to late summer for a fall crop.

If you should have a particularly warm spell, plants may “bolt” or suddenly go to seed, causing maturity to come to a grinding halt. Foliage and blossoms may be usable, but immature bulbs will probably be a loss.

And finally, weed the garden regularly to reduce competition for water, deter pests, and inhibit moisture buildup that can lead to disease, especially of a fungal nature.

Propagation

The best way to grow F. vulgare varieties is from seed.

It is possible, but challenging, to start with a root cutting, or division of the crown, the part where the stems meet the roots.

However, these plants have long, fragile taproots and don’t handle disturbance well. So, while you may be able to take a cutting or make a division, it may not transplant successfully.

Unlike some fruiting plants, the seed of fennel and its fruit are one and the same, so the words are used interchangeably.

Fennel seeds can be harvested from plants after the flowers fade, or purchased from quality purveyors.

Pests and Diseases

When you start with quality seed, cultivate during cool weather, provide rich soil that drains well, don’t overwater, and keep the garden free of weeds, pests and disease issues should be minimal.

However, sometimes even with the best intentions, we have to contend with herbivores, insect pests, and diseases often borne by these pests.

You may find that rabbits take quite an interest in your plants, but deer and groundhogs don’t seem to care for its aroma.

Some pests to be aware of are:

- Aphids

- Slugs and snails

- Swallowtail butterfly caterpillars, aka parsley worms

- Thrips

To eradicate sap-sucking aphids and thrips, a strong stream of water from the hose may do the trick. An application of organic neem oil may be a beneficial treatment for large outbreaks.

For slugs and snails, you can set traps and then discard those you catch.

As for the swallowtail butterfly caterpillar, you may have mixed feelings. It’s likely to feed on the aphids, but it is also going to feast on the foliage.

If you decide you just can’t share, either pick them off by hand, or try adding a few attractions to the yard like a bird feeder or an inviting birdbath, and let avian visitors help keep them in check.

In addition, there are a few diseases that may present themselves, including:

- Cercospora leaf blight

- Damping off

- Downy mildew

- Powdery mildew

- Rust

We’ve already talked about damping off, a fungal disease that kills seedlings, and for which there is no cure.

These are primarily fungal conditions, with the exception of downy mildew, which is caused by a water mold called an oomycete.

All affect the foliage, causing discoloration and often deformity. They are likely to respond favorably to fungicides formulated for edible plants.

III. Uses and Benefits

- Medicinal uses

Fennel was prized by the ancient Greeks and Romans, who used it as medicine, food, and insect repellent. Fennel tea was believed to give courage to the warriors before battle. According to Greek mythology, Prometheus used a giant stalk of fennel to carry fire from Mount Olympus to Earth. Emperor Charlemagne required the cultivation of fennel on all imperial farms.

Florence fennel is one of the three main herbs used in the preparation of absinthe, an alcoholic mixture which originated as a medicinal elixir in Europe and became, by the late 19th century, a popular alcoholic drink in France and other countries. Fennel fruit is a common and traditional spice in flavored Scandinavian brännvin (a loosely defined group of distilled spirits, which include akvavit). Fennel is also featured in the Chinese Materia Medica for its medicinal functions.

- Culinary uses

The bulb, foliage, and fruits of the fennel plant are used in many of the culinary traditions of the world. The small flowers of wild fennel (known as fennel “pollen”) are the most potent form of fennel, but also the most expensive. Dried fennel fruit is an aromatic, anise-flavored spice, brown or green when fresh, slowly turning a dull grey as the fruit ages. For cooking, green fruits are optimal.

The leaves are delicately flavored and similar in shape to dill. The bulb is a crisp vegetable that can be sautéed, stewed, braised, grilled, or eaten raw. Tender young leaves are used for garnishes, as a salad, to add flavor to salads, to flavor sauces to be served with puddings, and in soups and fish sauce. Both the inflated leaf bases and the tender young shoots can be eaten like celery.

Fennel fruits are sometimes confused with those of anise, which are similar in taste and appearance, though smaller. Fennel is also a flavoring in some natural toothpastes. The fruits are used in cookery and sweet desserts.

Many cultures in India, Afghanistan, Iran, and the Middle East use fennel fruits in cooking. In Iraq, fennel seeds are used as an ingredient in nigella-flavored breads. It is one of the most important spices in Kashmiri cuisine and Gujarati cooking. In Indian cuisine, whole fennel seeds and fennel powder are used as a spice in various sweet and savory dishes. It is an essential ingredient in the Assamese/Bengali/Oriya spice mixture panch phoron and in Chinese five-spice powders.

In many parts of India, roasted fennel fruits are consumed as mukhwas, an after-meal digestive and breath freshener (saunf), or candied as comfit. Fennel seeds are also often used as an ingredient in paan, a breath freshener most popularly consumed in India.

Fennel leaves are used in some parts of India as leafy green vegetables either by themselves or mixed with other vegetables, cooked to be served and consumed as part of a meal. In Syria and Lebanon, the young leaves are used to make a special kind of egg omelette (along with onions and flour) called ijjeh.

Many egg, fish, and other dishes employ fresh or dried fennel leaves. Florence fennel is a key ingredient in some Italian salads, or it can be braised and served as a warm side dish. It may be blanched or marinated, or cooked in risotto.

Fennel fruits are the primary flavor component in Italian sausage. In Spain, the stems of the fennel plant are used in the preparation of pickled eggplants, berenjenas de Almagro. A herbal tea or tisane can also be made from fennel.

On account of its aromatic properties, fennel fruit forms one of the ingredients of the well-known compound liquorice powder. In the Indian subcontinent, fennel fruits are eaten raw, sometimes with a sweetener.

In Israel, fennel salad is made of chopped fennel bulbs flavored with salt, black pepper, lemon juice, parsley, olive oil, and sometimes sumac.

IV. Harvesting and Storage

Harvesting

You can pick the tender young shoots of common varieties to enjoy as tasty microgreens, while mature leaves are exceptional when chopped finely as a fresh herb.

Even the stems can be used, like tough celery, in slow-cooked dishes.

When harvesting, try not to take more than one-third of the entire plant at once to avoid shocking it into bolting, or prematurely running to seed.

You can also harvest the flowers to use fresh, or to dry and scrape off the pollen, which has the most intense anise-type flavor of all.

Collect the seeds when they’re green, just after the pods form, or wait until the pods turn brown and the seeds are dry.

For Florence varieties, gather the bulbs when they are about the size of a tennis ball, or at most, four inches across.

Slice each off at ground level with a clean knife, and slice the elongated stems and profusion of leaves off at about three to six inches above the bulb. All parts can be used!

When they’re harvested young, these plants are finished. There will be no flowers, and therefore no seeds.

If you are growing this type and want flowers and seeds, simply allow some of the bulbs to get larger, and soon flower buds will form, bloom, and set fruit.

Plants may be able to tolerate a light frost, but if there’s a hard freeze predicted, harvest what you can in a hurry, including digging up the roots to use as you would carrots, if you’re so inclined.

Storing and Preserving

To store Florence fennel, cut the long stalks off, leaving about two inches above each bulb.

I like to slice the bulbs of Florence types in sections about an inch thick, and store them covered in water in an airtight container in the fridge.

You can also store whole bulbs in the fridge for three to five days, or up to a week and a half if you place a damp paper towel over them.

As for cut foliage, it’s quite delicate, and goes limp quickly. Plan to use it the same day you pick it. Keep it ready by cutting stalks and placing them in a container of water until needed.

Snip off the feathery foliage you want for use in salads and as fragrant garnishes, or toss it into savory cooked dishes as you would with dill.

The stalks can be a little tough, so they’re best in cooked dishes. Some folks dry them in a low oven at about 200°F, for two hours or so.

Fresh, they keep for up to two weeks in the fridge, and are a healthy addition to slow-cooked soups and stews.

Green fennel seeds should be kept in the fridge and consumed within a week of picking.

Pollen scraped and gathered from dry flowers saves well in a sealed jar for approximately two years.

Dry seeds should remain robust and aromatic for several years when stored in an airtight jar. Keep them handy to use as a spice, or to chew a few as a digestive aid and breath freshener.

Find Where to Buy the Best Florence Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Leave a Reply